Subtractive design is the process of removing imperfections and extraneous parts in order to strengthen the core elements. You can think of a design as something you build up, construct and let grow, but it’s pruning away the excess that gives a design a sense of simplicity, elegance, and power.

Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.

—Albert Einstein

Make everything as simple as possible, and then a little simpler.

—Hectóre Blivand

First let's look at the theory behind this idea to see why designers in many fields often think in terms of negatives (subtracting things) rather than positives (adding things). Then let's look at several successful subtractive designs so we know what to aim for. Finally, I'll discuss why subtractive design often breeds controversy.

Why Subtraction?

Designers in many fields, not just games, often think in terms of negatives (subtracting things) rather than positives (adding things). Design is creating a form (a game in our case) that fits a context. There isn’t just one boundary we have to check between form and context though, there are infinitely many. Is our game easy enough to learn? Does it have the desired amount of strategy or depth? Does it appeal to the intended age-group? Is it cheap enough to make in both time and money? Is it aesthetically pleasing? Do the aesthetics help the player understand how to play the game? Do the mechanics work well with each other? Do they require the desired amount of dexterity? The list goes on.

We first come up with a design that might fit all the requirements. Sometimes this comes from the intuition of a designer who has internalized all those forces and somehow spits out a new answer. More likely, we start with something pretty well established so that we know it solves many of the requirements already. That’s how genres, sequels, and remakes help us make good (but not necessarily new) designs.

Once we have something, we have to evaluate how good our design is. Does our form actually fit the context? Architect Christopher Alexander had some choice words on this subject in his Notes on the Synthesis of Form:

We should find it almost impossible to characterize a house which fits its context. Yet it is the easiest thing in the world to name the specific kinds of misfit which prevent good fit. A kitchen which is hard to clean, no place to park my car, the child playing where it can be run down by someone else’s car, rainwater coming in, overcrowding and lack of privacy, the eye-level grill which spits hot fat right into my eye, the gold plastic doorknob which deceives my expectations, and the front door I cannot find, are all misfits between the house and the lives and habits it's meant to fit. These misfits are the forces which must shape it, and there is no mistaking them. Because they are expressed in negative form they are specific, and tangible enough to talk about.

Alexander explains that when a misfit occurs, we are able to point at it specifically and describe it. When we instead try to explain what a good fit would be like, we’re often reduced to generalities that are hard to act on.

With this in mind I should like to recommend that we should always expect to see the process of achieving good fit between two entities as a negative process of neutralizing the incongruities, or irritants, or forces, which cause misfit.

Ico

When Fumito Ueda designed Ico, he did not start with a list of everything the game should have. Instead, he started with the core idea that it should be a platform / puzzle game about a boy and a girl, and that the game should have emotional impact by creating an environment that had its own believable reality to it. Using other platform and puzzle games a point of reference, he then started subtracting away everything that was extraneous to his core idea.

Other games might use a nine act structure where the story starts in a village, then you go into the forest, then you find a castle, then escape back to the forest, and so on. Ueda was conscious of this, but cut everything except the castle, so that the castle could be fully realized, fully polished, and seem to be a character of its own. Other games have NPCs that stand around and give you hints, but when you see the same character say the same lines over and over, it takes you out of the fictional world. Ueda stated from the beginning that he would have no such NPCs. Other games may have an army of different enemies, but Ueda found that puzzles were enough, and only one type of enemy was needed. He also removed the health meter, inventory screen, and even background music from his design—all things that come standard in other games.

Another misfit that was on Ueda’s mind was bad animation. If the core idea is to show a boy and a girl escaping a castle together, and we want a sense of immersion and reality, then nothing in the boy’s or girl’s animations can stand out as strange. His team spent a great deal of effort on the character animations, especially those where the girl and boy interact, because any imperfections there would have been glaring.

I learned all this from Ueda’s 2004 presentation at the Game Developer's Conference, but there was one more detail that stuck with me. He showed us a screenshot of one room in the castle and asked us what was wrong with it. I thought it looked pretty good. Ueda then pointed out that there was a chair in the screenshot that didn’t look very good. He said when something like this happens, you have to decide whether you have the time and resources to fix it (make the chair more beautiful and believable) or cut it. In this case, he cut the chair.

For all Ico’s cuts, you’d think it would be a game with nothing much left. And yet it received high critical acclaim as powerful game. The important elements are executed unusually well, and the unimportant elements—I couldn’t find any.

Braid

Jonathan Blow’s Braid shows a similar reductionist design with a similarly powerful result. The core concept behind Braid is the manipulation and rewinding of time without the need of a meter to limit the mechanic. You can rewind time as much as you like, as often as you like, and the difficulty of the game comes in puzzles that test just how clever you are with this manipulation. Because time manipulation is the core concept, Braid explores time mechanics fully. On one level walking left reverses time while walking right moves time forward. On another, some objects are immune to the time shifting. Each level investigates a new idea.

What’s remarkable about Braid is how many things Jonathan Blow cut away. There are no “lives,” because the entire idea of lives is incompatible with having infinite time-rewind powers. There are only about five types of enemies, much fewer than is usual for a 2D platform game. There are only two action buttons: jump and rewind time (though there is a third button used later in the game to put down an object).

What’s most strikingly minimal of all in Braid is the level design. Each level is as small as it can possibly be, containing as few elements as it could realistically contain while still being interesting. This gives the game’s construction the feel of a tight short story: every part is there for a reason and there’s nothing extra. Even the quantity of levels follows this logic—when the game is done exploring new time mechanics, it ends. It feels no need to make us fight hundreds of blue slimes in order to level up to fight red slimes.

By trimming the fat in action buttons, UI, enemy types, level size, and level quantity, Braid feels vigorous in the way Strunk and White meant in The Elements of Style, 4th Edition, as seen in his discussion of omitting needless words.

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

Portal

Valve’s game Portal is another example of a compact, distilled design. The core idea is that you can shoot two kinds of portals (orange and blue) and then walk through one to come out of the other. You have no actual weapons, no inventory screen, no NPCs to talk to, not even any enemies aside from the occasional turret and the final boss. The controls are as simple as they can be, with action buttons only for shooting the two kinds of portals, for jump, and for using objects (open door, pick up crate, and so on).

Portal’s environments are sparse and sterile, containing practically nothing except for elements that are part of puzzles, elements that offer you visual cues as hints about what you should do, and elements to convey the story. That there’s nothing extra puts all the emphasis on the portal mechanic itself, which is incredibly fun. Like Braid, Portal explores its mechanic fully, doing just about everything you can think of to do with portals, then it gracefully ends without overstaying its welcome or subjecting you to filler content.

Team Fortress 2

Valve’s Team Fortress 2 has a lot of things going for it, but it’s specifically the approach to map design that stands out as a case for subtractive design. Most games of this type would offer as many maps as possible. More is seen as better by marketing departments, after all. Valve deliberately limited the game to only six maps when it shipped, though.

One benefit of fewer maps in a multiplayer game is less fragmentation of the player-base. If there are hundreds of maps it can be hard to find anyone who wants to play the particular map you do. But more to the point, Valve knew that in most multiplayer games, the community settles on just a very few maps they play endlessly. If this is a known phenomenon in so many games, why make tons of maps?

By sticking to only six, an unusually small set for this type of game, Valve had time to make these the best, most polished maps they could. Fewer maps means each one received more attention from playtesters, artists, and designers. The process of playtesting a map is, itself, a subtractive design exercise. You play it as much as possible in as many different ways as possible, looking for bugs, exploits, and defects that make the gameplay less fun or less strategic. The more you limit the number of maps, the more defects you can fix in each one.

Game designers should look outside the field of games for inspiration and ideas, so I'll present two examples of non-game software.

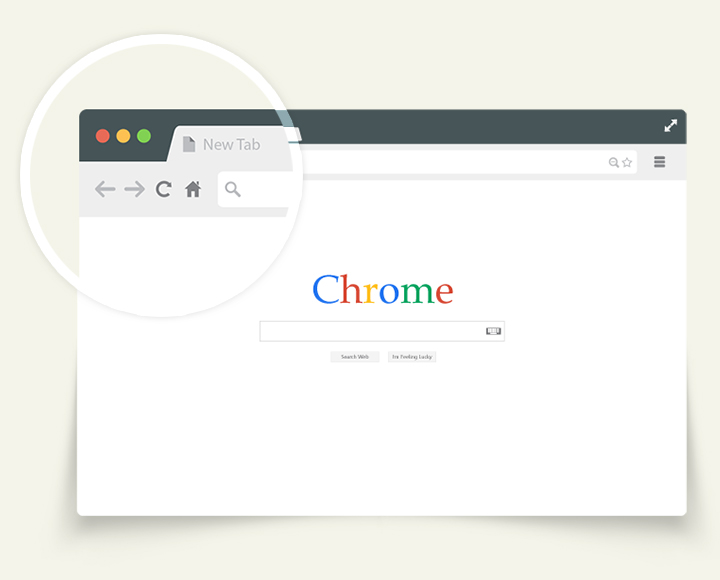

Google Chrome

Google has a simple elegance in many of its products, and the Google Chrome web browser is a great example of subtracting the debris that other browsers had. Why do we need two different fields at the top of a browser (one to search the web, one for the URLs) when they could be combined into one? Google Chrome does this to save space and reduce clutter. There is no chance of confusing the two uses in one field anyway, because search terms have spaces between them while URLs have things like “.com” in them.

The core idea behind Google Chrome is “get out of the way and remove debris whenever possible.” The “find” field only shows up when you press cmd-F, otherwise it’s not even there to get in the way. When you mouse over a link, the status bar showing where the link points to shows up in small box in the corner, but this box fades away entirely at other times. Chrome also got rid of these things from Internet Explorer 6:

- file menu

- edit menu

- view menu

- favorites menu

- tools menu

- help menu

- homepage button (you can turn it on in the options)

- search button (just type in the URL bar to search)

- favorites tab button

- history button

- mail button

- print button

- edit button

- messenger button (what is this doing here??)

- the word “address” labeling the address bar

- status bar

It added these interface elements:

- menu button for options about the current page

- menu button for options about Google Chrome in general

- new tab button.

Does this simpler interface with all the debris removed mean that Google Chrome is less powerful or less advanced than its competitors? Quite the contrary. Under the hood, it separates each tab into a new process, meaning that one pesky website can’t cause your entire browser to crash. It also does a better job of preventing memory leaks than its competitors with better memory garbage collection. The power is out-of-sight, and the browser UI is as minimal as possible so that everything is there for a purpose, everything with no purpose is gone, and the things that are there are high quality.

Other browsers have since become more like Chrome. Unified search/URL bars and sandboxed tabs are now standard.

Apple's Time Machine

Apple also has a long history of simple and elegant products. It might be the best company in the world at making complicated things simple and elegant. Apple has done that several times by crafting new kinds of interfaces. They created the first personal computer to use a mouse. The iPod’s scroll wheel was a simple way to scroll through hundreds of songs. The breakthrough of the multitouch interface on the iPhone shook up the phone industry. I’ll use a less familiar example though: Apple’s Time Machine software.

The core concept behind this built-in part of a Mac’s operating system is “make it so easy to back up your data that you’ll actually do it.” The problem with data backup software is not that it doesn’t do enough things, it’s that the average user is too lazy to ever actually do it at all.

Apple’s solution is a “zero click” interface, though maybe it’s more fair to call it one click. When you plug in any drive, a pop-up asks you if you’d like this to be your Time Machine drive to back up your files (it doesn’t ask if you’ve already set a Time Machine drive, of course). If you say yes, that’s all there is for you to do. Time Machine will then back up all your computer’s files and keep running backups every hour for the last 24 hours, daily backups for the last month, and weekly backups forever, until the drive is full.

The interface for recovering old files is slick and useful, but it’s the “zero click” setup that makes the feature so practical. Now that's subtractive.

Common Themes

There’s something all these examples have in common. Apple’s Time Machine and Google Chrome are both very sophisticated under the hood, even though they present simple interfaces to the user. Team Fortress 2 is not more shallow for its decision to launch with fewer maps; it’s actually deeper because of that decision. Portal and Braid did not, as Professor Strunk would say, “avoid all detail and treat their subjects only in outline.” Quite the contrary. Portal and Braid each fully explore their concepts—more fully than most larger, bloated games usually explore theirs. And finally, Ico’s sense of reality, immersion, and emotional power is not less because it subtracted all the extraneous elements; it's more. In each case, subtracting did not leave us lacking, it enhanced the experience.

The Controversy

Subtractive design is not all rainbows and puppies though. By fully committing to this idea, you are more likely to encounter resistance on your game development team, with your publisher, and with your players. The reason is that when we use vague language, it’s easier to get an agreement. When we use very honest, precise language, it’s easier for someone to realize that they disagreed all along.

“Some amount of collateral damage is expected in the mission.” Sure, ok.

“We are going to kill innocent people on this mission.” Wait, really?

When we distill a design down to the core concepts and remove the extraneous, it forces us to admit and agree what the core concepts actually are. For example, as designer of Street Fighter HD Remix, I made the statement that performing difficult moves is not part of the core concept of the game. It’s an imperfection that should be removed, so that there can be more focus on the essence of the game: strategy. Clearly, that is a troublesome statement if you believe that performing difficult moves is part of the essence of the game. I think subtracting some emphasis on that aspect enhanced the final product though.

Likewise, in StarCraft, the ability to play not just fast, but extremely fast is highly rewarded. When Blizzard made StarCraft 2, it had to decide what the game is really about at its core. Maybe a game in the “real-time strategy” genre should focus a bit more on strategy and less on extremely fast clicking? Creating more user-friendly features such as multiple-base selection, auto-mine, and no cap on the number of units you can select all point to them thinking that. (Though they also added other features intentionally meant to add more clicks, so I don't know.) The point is that during development, the mere proposal of multiple-base selection and automine raised deep questions about what the the game is really about. Is StarCraft really about strategy? Or is it equally about rewarding the most actions per minute that you can enter? It’s easier to agree that we like StarCraft overall (vague) than it is to agree on whether a new version of the game should or shouldn’t remove the emphasis on certain skills.

The card game Magic: the Gathering has an even deeper conflict about what it’s really about. When it comes to the wording on the cards, the Magic team has made great strides over the years to remove unnecessary words, creating as many simple, elegant cards as they can. Compare the original wording of the card Control Magic to the current wording:

But on a more zoomed out level, what is Magic really about? Is it about delivering the most fun gameplay experience possible to its players? Or selling collectable items that have artificial scarcity? One gets in the way of the other, as it stands. I propose that the essence of customizable card games is the gameplay, and that collectability is purely a barrier between players and the game. Making such a statement naturally creates a firestorm of argument because it forces us define what the essence of a game is. That can be uncomfortable to do, but necessary for knowing how to design something.

For my customizable card game called Codex, I'm subtracting out all the chaff cards, and subtracting out the entire concept of collecting rares. It delivers the most gameplay possible in the fewest cards, which makes it the opposite of the standard approach of bloat in CCGs.

Closing Thoughts

It’s easiest to get people to agree on vague concepts. “The game we’re making is a platformer with exploration, but also with fast action and time pressure. It has an epic story of course, but also a personal story. The game is really challenging, but it’s for everyone to enjoy. It has 20 enemy types and 20 weapons including a kazoo and a kitchen sink.” What’s not to agree with? There’s something for everyone.

A more direct approach would be to find a starting point, whether it’s another game’s design or something you generate yourself. How to do that is another topic entirely. But once that core concept is in place, stay on the lookout for things that get in the way. Is every button press really needed? Every menu item? Every HUD element? Are there features that you just don’t have time to do justice? (Let’s add multiplayer!) If the game is about testing player skill, is it testing the only the skills you want to test? If it’s about story, are all the scenes contributing to that story? Do you need all the mechanics you planned, or will a smaller set (easier for the player to remember and learn) suffice? Is there a way to make your levels smaller or shorter by removing or shrinking areas that do not have much purpose?

Getting rid of all that stuff means there are fewer things for the player to misunderstand, and makes it more likely that the vision of the game in your head actually ends up in the player’s head, too. It takes some courage and pain to commit to a specific idea and subtract the rest away, but I think Ico, Braid, Portal, Team Fortress 2, Google Chrome, and Apple's Time Machine all demonstrate that doing so can lead to powerful, memorable experiences.