Balancing a competitive multiplayer game is difficult—really, really difficult. In this article I’ll define the terms that will help us discuss the topic, then in the second and third articles I’ll explain what counts as balance and some techniques to work toward it. Then in the fourth article, I’ll try to impress upon you what deep trouble we’re really in. It's a wicked problem that by its very nature is resistant to complete mathematical analysis. We'll have to do it different way.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Definitions (this article)

Part 2: Viable Options

Part 3: Fairness

Part 4: Intuition

4-page printable handout

See also:

Game Balance and Yomi

First, the terms. Let’s start with balance and depth as defined by my former selves:

A multiplayer game is balanced if a reasonably large number of options available to the player are viable--especially, but not limited to, during high-level play by expert players.

—Sirlin, December 2001

A multiplayer game is deep if it is still strategically interesting to play after expert players have studied and practiced it for years, decades, or centuries.

—Sirlin, January 2002

This definition of balance is pretty good, but there are two concepts hiding inside that term viable options. On one hand, I meant that the game doesn’t degenerate down to just one tactic, and on the other hand, I meant that if there are lots of characters to choose from in a fighting game or races to choose from in a real-time strategy game, many of those characters/races are reasonable to pick. Let’s call the first idea viable options and second idea fairness in starting options, or just fairness for short.

Viable Options: Lots of meaningful choices presented to the player. They should be presented with enough context to allows the player to use strategy to make those choices.

Fairness: Players of equal skill have a roughly equal chance at winning even though they might start the game with different sets of options / moves / characters / resources / etc.

Viable Options

The requirement that we present many viable options to the player during gameplay is what Sid Meier meant when he said that a game is a series of interesting decisions (a multiplayer competitive game, at least).

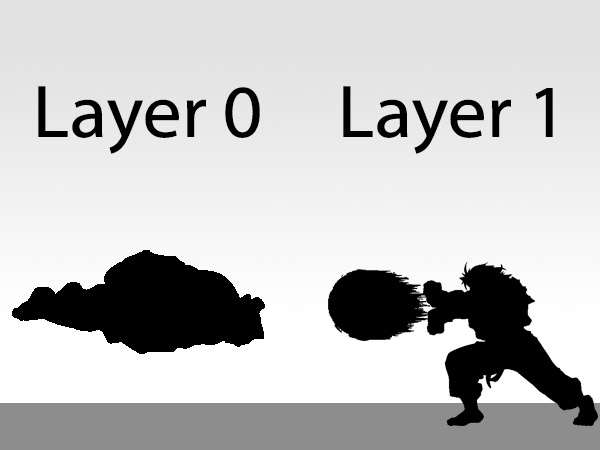

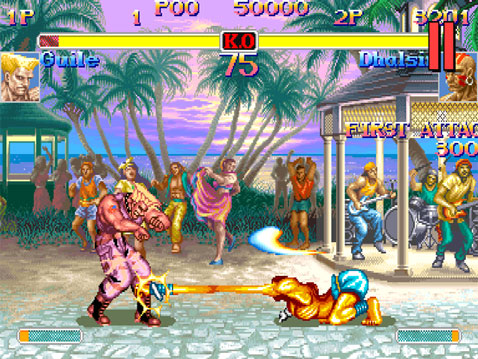

If an expert player can consistently beat other experts by just doing one move or one tactic, we have to call that game imbalanced because there aren’t enough viable options. Such a game might have thousands of options, but we only care about the meaningful ones. If those thousands of options all accomplish the same thing, or nothing, or all lose to the dominant move mentioned above, then they are not meaningful options. They just get in the way and add the worst kind of complexity to the game: complexity that makes the game harder to learn yet no more interesting to play.

For the sake of depth, we also hope that the player has some basis to choose amongst these meaningful options. If the game at hand is a single round of rock, paper, scissors against a single opponent, there is nearly no basis to choose one option over the other so it’s hard to apply any kind of strategy. And yet a game of Street Fighter might be decided by a single moment when you choose to either block, throw, or Dragon Punch, or a game of Magic: the Gathering might be decided by a single Master of Predicaments decision. These examples at first glance look like the rock, paper, scissors example, but the decisions take place inside the context of a match that has many nuances where each player is dripping with cues about their future behavior. In Street Fighter and Magic, the player does have basis to choose one option over the other, and more than one choice is viable, we hope.

Also for depth, we prefer if the meaningful choices depend on the opponent’s actions. Imagine a modified game of StarCraft where no players are allowed to attack each other. All they can do is build their base for 5 minutes, then we calculate a score based on what they built. There are many decisions to make in this game, and it might have several paths to victory, but because these decisions are purely about optimization—more like solving a puzzle than playing a game—they make for a shallow competitive game. Fortunately, in the actual game of StarCraft, you do need to consider what your opponent is building when you decide what to build.

While we require many viable options to call a game balanced, the requirement about giving the player a context to make those decisions strategically and the requirement that the decisions have something to do with the opponent’s actions are really about depth. They’re worth pointing out though because we should attempt to increase the depth of the game as we balance it, not decrease it.

Fairness

Fairness, in the context I’m using it here, refers to each player having an equal chance of winning even though they might start the game with different options. In Street Fighter, each character has different moves, in StarCraft each race has different units, and in World of Warcraft, each arena team has different classes, talent builds, and gear. Somehow, all of these very different sets of options must be fair against each other.

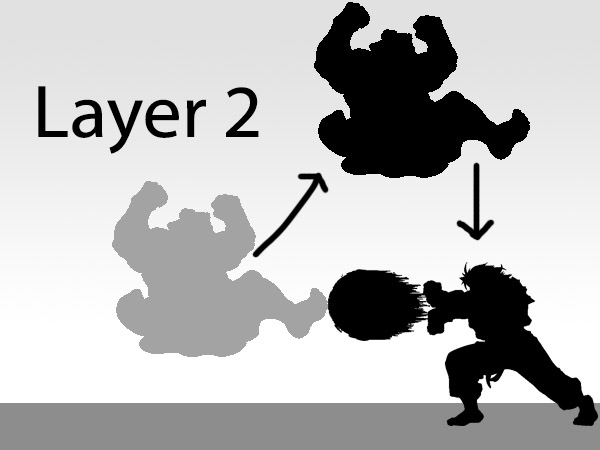

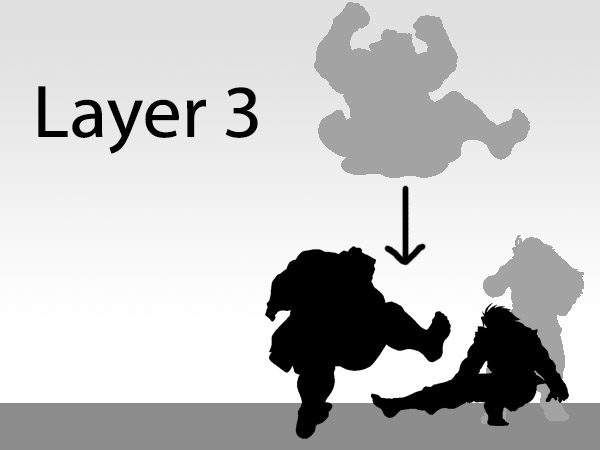

I want to stress that I am only talking about options that you’re locked into as the game starts. That’s a very important distinction. Options that open up after a game starts do not necessarily have to be fair against each other at all. Imagine a first-person shooter with 8 weapons that spawn in various locations around the map. Two of these weapons are the best overall, 3 are ok but not as good as the best weapons, and the remaining 3 are generally terrible but happen to be extremely powerful against one or the other of the 2 best weapons.

Is this theoretical game balanced? It certainly might be, meaning that nothing said so far would disqualify it. A designer could decide that they want all weapons to be of equal power, but they need not decide that as long as each weapon is still a viable choice in the right situation. It might be fine to have two powerful weapons that players compete over, a few medium power weapons that are still ok, and some weak weapons that allow players to specifically counter the strong weapons. There could be a lot of strategy in deciding which parts of the map to try to control (in order to access specific weapons) and when to switch weapons depending on what your opponents are doing.

By contrast, a fighting game with 8 characters designed by that scheme is not balanced because it fails the fairness test. Players choose fighting game characters before the game starts, but they pick up weapons in the first-person shooter example during gameplay. Being locked into a character that has a huge disadvantage against the opponent’s character is unfair.

Games that let players start with different sets of options are inherently harder to balance because they must make those sets of options fair against each other in addition to offering the players many viable options during gameplay.

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Games

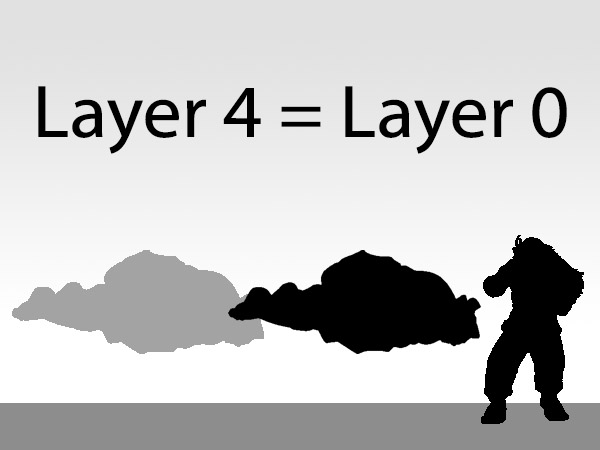

Let us call symmetric games the types of games where all players start with the same sets of options. We’ll call asymmetric games the types of games where players start the game with different sets of options. Think of these terms as a spectrum, rather than merely two buckets.

Symmetric Asymmetric

<---------------------------------------------->

Same starting options Diverse Starting options

On the left side of the spectrum, we have games like Chess. In Chess, each side starts with exactly the same 16 pieces. The only difference between the two sides is that white moves first. Because of this different starting condition, we shouldn’t say that Chess is 100% symmetric, but it’s damn close. If Chess were the only game you had ever seen, you might think that the black and white sides are played radically differently; white sets the tempo while black reacts. There are entire books written about how to play just the black side. And yet if we zoom out to look at the many games in the world, we see that the two sides of Chess are so similar as to be virtually indistinguishable when compared to two races in Starcraft, two characters in Street Fighter, two decks in Magic: The Gathering, or two armies in Chess 2.

The more diversity in starting conditions the game allows, the farther to the right of our spectrum it belongs. So asymmetry, as we mean it here, is a measure of a game’s diversity in starting conditions. This is not meant to be an exact science, so there is no specific formula to determine where a game belongs on this spectrum, but it’s a handy concept anyway.

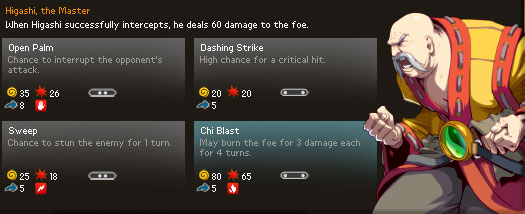

Let’s look at a few examples. StarCraft has three very diverse races so it belongs toward the right side of our spectrum. That said, even if the three races were as different as imaginable from each other, the number three is small enough that we shouldn’t put it at the far right (admittedly, this is a judgment call). Fighting games can have dozens of characters that play completely differently and they tend to have more asymmetry than most other types of competitive multiplayer games.

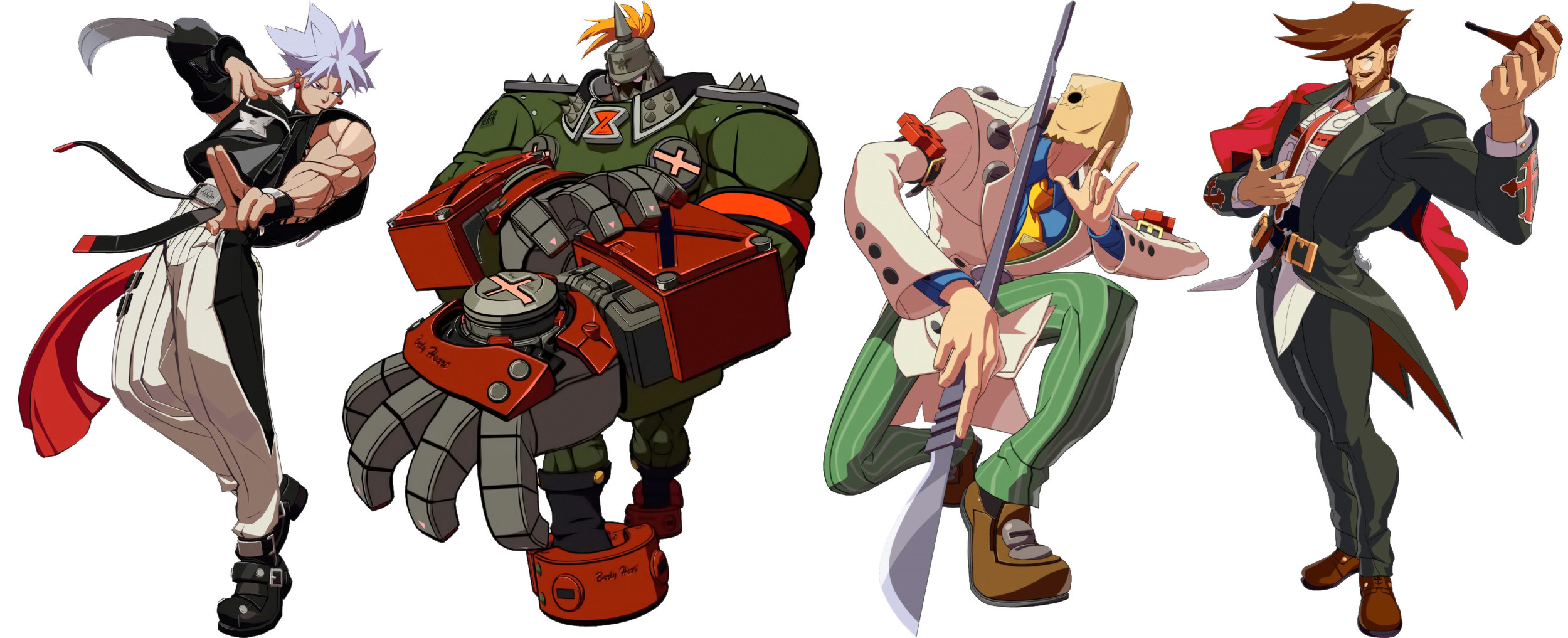

That said, individual fighting games can vary quite a bit in just how asymmetric they are. Virtua Fighter, for example, is an excellent and deep fighting game, but the diversity of characters is relatively low compared to other fighting games. All characters have a similar template compared to Street Fighter where some characters have projectiles, or arms that reach across the entire screen, or the ability to fly around the playfield. Meanwhile, Guilty Gear, a fighting game you might not have have heard of, has more diversity than any other game in the genre that I know of. One character can create complex formations of pool balls that he bounces against each other, another controls two characters at once, another has a limited number of coins (projectiles) that power up one of his other moves and a strange floating mist that can make that powered up move unblockable. It’s almost as if each character came from a different game entirely, yet somehow they can compete fairly against each other. Guilty Gear is possibly all the way to the right of our chart because it has both wildly different starting options (characters) and many of them (over 20!).

Magic: The Gathering is also extremely asymmetric in the format called constructed where players bring pre-made decks to a tournament. The variety of possible decks is staggering and tournaments usually have several different decks of roughly equal power level, even though they play radically differently.

First-person shooters tend to be very far toward the symmetric side of the spectrum, usually offering the same options to everyone at the start, except for spawning location. Remember that picking up different weapons during gameplay, or even changing classes during gameplay in Team Fortress 2, does not count as asymmetric for our purposes. (Again, because those different options don’t need to be exactly fair against each other.) Also, first-person shooters that do have asymmetric goals for each side often make the sides switch and play another round with roles reversed so that the overall match is symmetric.

Now that we’ve mapped out where some games fit on our spectrum, remember that this is not a measure of game quality. If your favorite games appear on the left (symmetric) side, that does not mean they are bad. If you like StarCraft more than Guilty Gear, you do not need to be upset that Guilty Gear is “more asymmetric.” The spectrum is simply meant to give us an idea about how different the starting options of a game are, not about the depth or fun of the game. That said, I do personally prefer asymmetric games and they are inherently more interesting to me.

No matter where a game appears on this spectrum, it still needs offer many viable options during gameplay to be balanced. In addition to this, the farther a game is to the right of the spectrum, the more it needs to care about balancing the fairness of the different starting options. In the next part of this series, I’ll talk about how we can design games that make sure to offer enough viable options and in the article after that, I’ll explain how we can attempt to create fairness in those pesky asymmetric games.