Puzzle Strike’s gameplay centers around the crash gem system which was inspired by Puzzle Fighter (which I was also lead designer of). The dynamics that result from it are interesting when played at high skill level or a low skill level so that gives the game a solid foundation to appeal to hardcore players and casual players. I’ll explain much more about what goes into pleasing each audience, but first let’s examine the crash gem system.

Crash Gem System

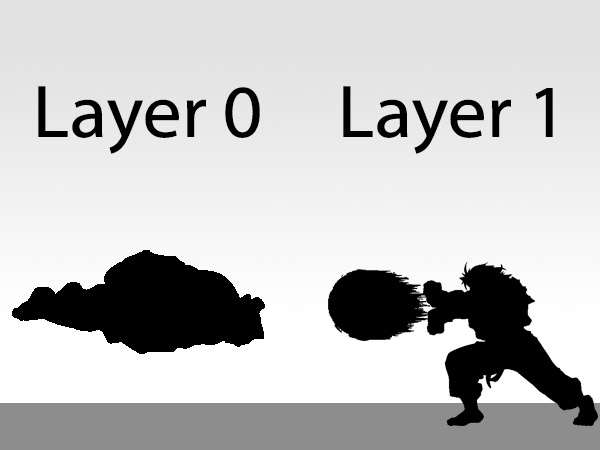

Gem Pile

Each player has a gem pile zone. Your gem pile fills up over time and if you end a turn with too many gems, you lose. Just before you lose, you’re usually at your most powerful though. You can use crash gems to break (remove) your gems and send them to an opponent. The more gems you have, the more ammunition you have. Also, the height bonus rule lets you draw more chips the more gems you have in your gem pile. Drawing more chips gives you a higher chance of drawing crash gems and other combo pieces that let you take more actions on your turn.

You always pass through a period of being very powerful just before you lose. Just before you lose is when you have the most ammo and the biggest height bonus to draw more chips. This specific way of handling the comeback mechanism tends to make games close and intense. This same mechanism worked great in Puzzle Fighter and my goal was to translate that to board game form.

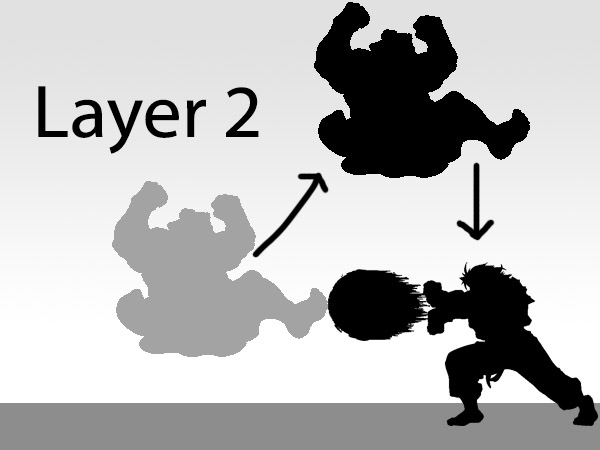

Combine

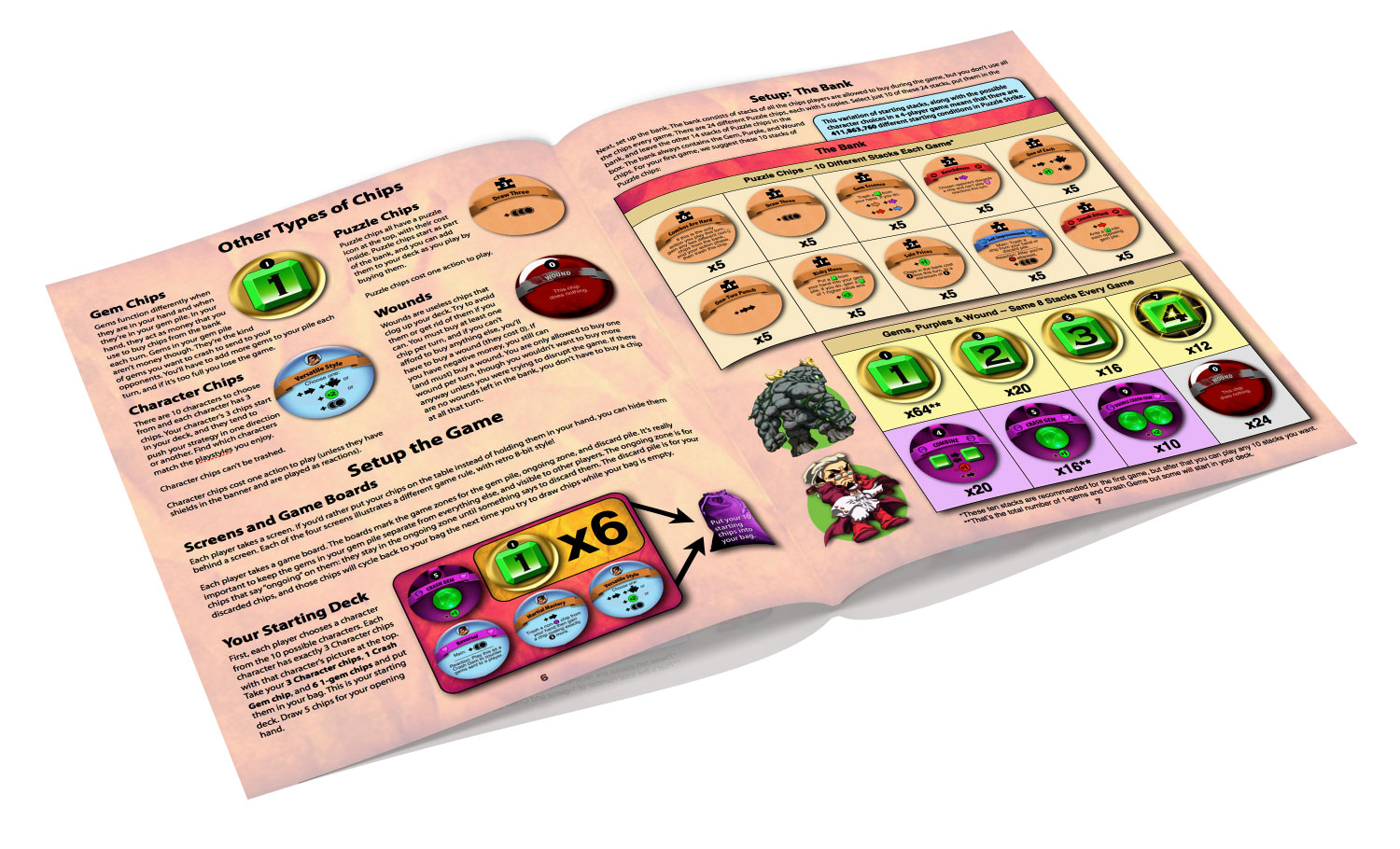

You can use a Combine chip to join two gems in your gem pile together into a bigger gem. For example, combining two 1-gems gives you a single 2-gem. Combining a 1-gem and a 2-gem gives you a 3-gem. The largest gem you can have is a 4-gem.

Combining makes your crashes stronger. A crash gem only breaks open a single one of your gems. If you use it on a 1-gem, it only reduces your pile height by 1 and only sends 1 gem to your opponent. If you use it on a 4-gem, it reduces your pile height by 4 and it sends 4 1-gems to your opponent. Then your opponent will have to deal with combining those before they can easily crash them back.

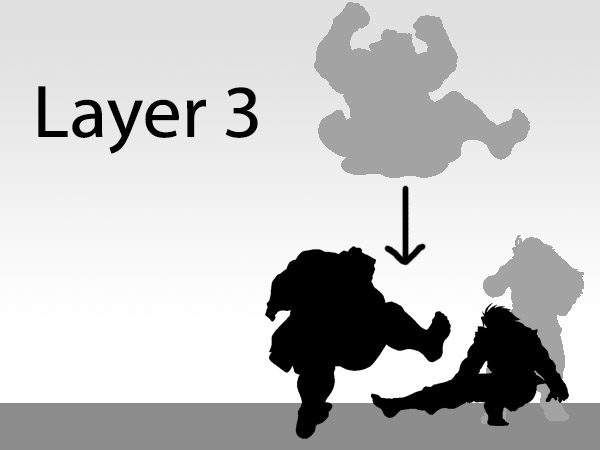

Counter-Crashing

Counter-crashing lets you stop an opponent’s crashed gems from reaching you. This lets you control the pace of the game in a strategic way. If no one ever crashed any gems, the game would end after 10 turns. That’s because each player antes a 1-gem at the start of their turn and the game ends whenever a player ends their turn with a pile height of 10 or more. If you crash gems at someone, you might end the game sooner because you’re giving your opponent gems. That said, your opponent might crash gems right back at you later, so on average it still might take about 10 turns to end.

Counter-crashing lets you actually extend the game though because it removes gems from the system. Whenever an opponent crashes gems to you, before those gems reach your gem pile, you have the opportunity to counter-crash. To do that, you use a crash gem to break gems in your own pile and cancel out some of the incoming gems. For example, if 3 gems were coming at you, if you crashed 2 gems of your own, you’d cancel out 2 of the 3 incoming gems. That removed a total of 4 gems from the system (2 in your gem pile, and 2 of the incoming gems). If you counter-crash repeatedly, you’re buying yourself more turns. If your strategy involves getting lots of money and spending it later, or building up a powerful combo and unleashing it later, you need to make sure there is a later. On the other hand, if your strategy is all about rushdown as hard as possible, you want to end the game as soon as possible before other players build up powerful late-game combos.

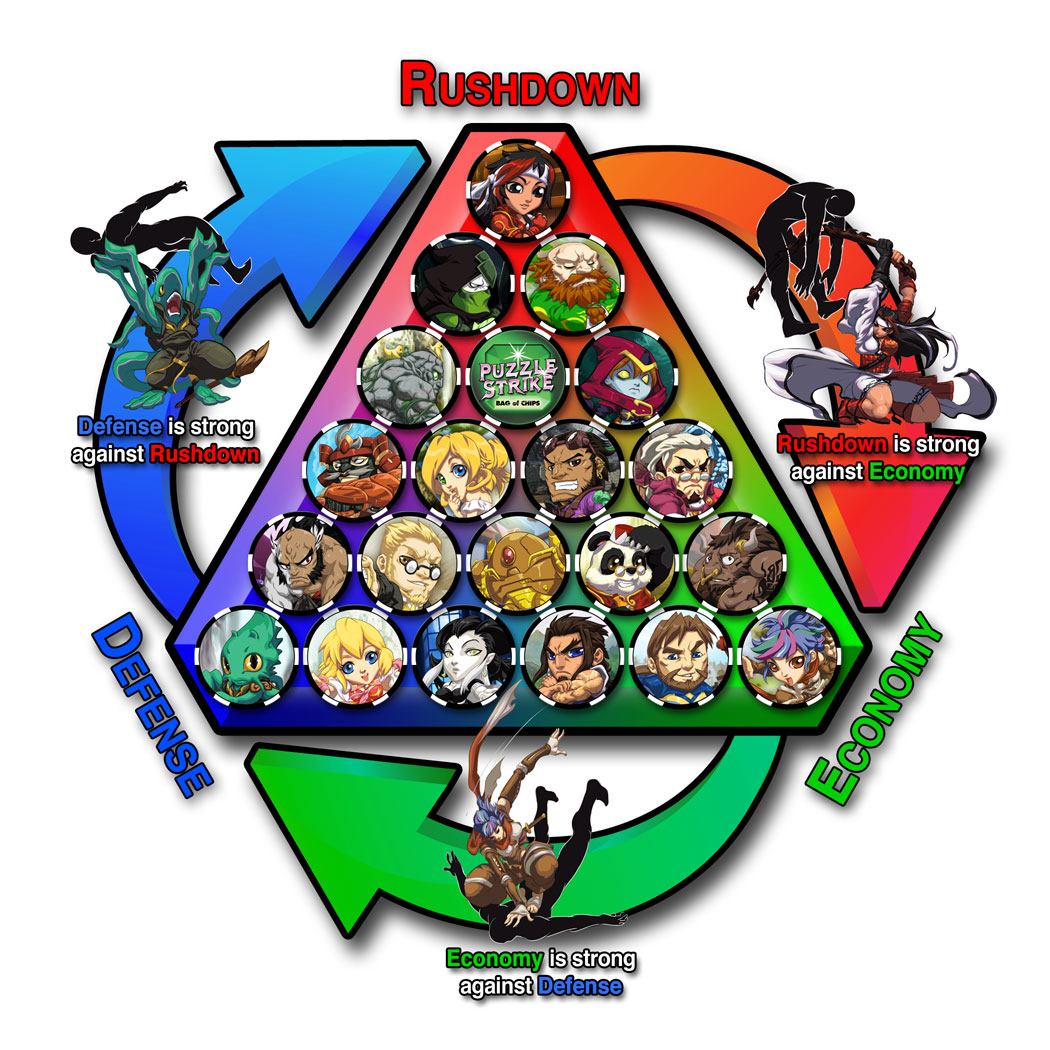

This diagram shows how rushdown, economy, and defense strategies relate to each other as well as how good each of the 20 characters is at executing that kind of strategy:

Money System

The money system is related to the crash gem system. You use money to buy more chips to add to your deck. Some of those chips give you more money themselves. Having a lot of money chips means you’ll be able to afford other more powerful chips that actually do something, but it’s a common mistake to put too much money in your deck in Puzzle Strike. You need to have Combines, Crash Gems, and various puzzle chips that actually do things.

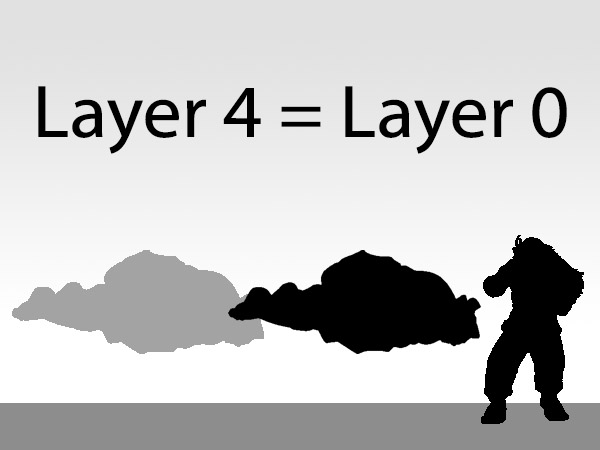

Crashing and combining gems affects how much money you have. Each time you crash a gem, you get an extra +$1 to spend that turn. (If you crash a larger gem such as 3-gem, you still get only $1.) On the other hand, each time you combine two gems, you get a -$1 modifier on your money that turn. Breaking open gems releases the gem power inside, but it requires energy to fuse two gems together. And if you counter-crash (break open your gems on another player’s turn while they’re crashing at you), you don’t actually get to used that released energy; the $1 bonus disappears before you get reach your next buy phase.

Here’s a short summary of that:

crash a gem: +$1

counter-crash a gem: +$0 (effectively)

combine two gems: -$1

What that means for strategy is that a rushdown strategy has a built-in drawback. If you want to be very aggressive, you’ll very quickly combine your gems into large gems and that will put you behind on money. You’ll then crash your big gems at your opponent(s) and hope to end the game very soon before your lack of money mattered.

The opposite strategy is to counter-crash a lot. That will remove gems from the system and give you more time (more turns) to develop a strong late-game deck. You’re still paying for the right to have more turns though in a way. At least you didn’t lose as much money as those paying for lots of combines, but you also didn’t gain the money you could have by crashing gems on your own turn.

Crashing gems on your own turn while only combining and counter-crashing the minimum amount you can get away with gives you the most money bonus. There are lots of tradeoffs here.

Tournament Level Play

It’s a good sign if a game is of high enough quality that it’s suitable to play at a tournament level. Even if you don’t care about ever attending a tournament for it, it means the game is solid enough to stand up to experts playing it. I find that reassuring because it means you can invest as much time in a game like that as you want and you don’t have to worry about it falling apart or becoming degenerate or boring if you ever get “too good” at it.

Here are the qualities I wanted, to ensure interesting play at high skill levels:

- Strategically interesting dynamics

- Player interaction

- Asymmetric design

- Getting to the meat of the game quickly

- Exciting moments built into the system

- Solid rules

Strategically interesting dynamics

We’ve already covered a lot of this part. The crash gem system and its interaction with the money system create unusual and interesting dynamics. There’s a lot for expert players to explore and a lot of ways they can express themselves in the game system.

Player interaction

A good competitive game needs lots of player interaction—the more the better. Games that are mostly solitaire that you play alongside other people and compare scores are really lacking in drama. They also lack in the primary skill test that you’d hope a competitive game would be about: how you act upon and react against an opponent.

Puzzle Strike’s core mechansim is inherently interactive. Crashing your gems at an opponent affects that opponent and they can counter-crash to interact back with you. Separately from this, there are also “attack” chips (red fist) and “defense” chips (blue shield) that add yet another layer of interacting and reacting to opponents. Puzzle Strike is not a passive-aggressive game of indirect interaction—it’s highly interactive so that there’s more ways to get advantages over your opponents and more ways they can avoid that, too.

Asymmetric design

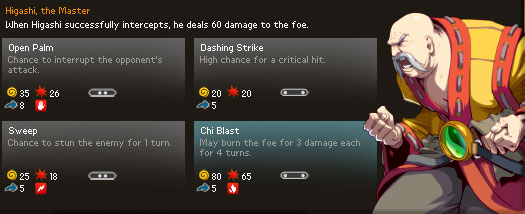

Symmetric games are kind of a flat experience after you’ve been exposed to just how rich and varied asymmetric games are. Puzzle Strike has 20 characters, which means there’s 210 different character matchups in just the 1v1 mode of the game. Different matchups play very differently, which is interesting. Different characters allow players to find ones that match their own personality and playstyle. Also, it’s a wonderful property in any asymmetric game that you can learn just one character (or perhaps a small number of characters) and yet still participate in a system far more varied and nuanced than one without different characters to choose from.

Or to put it more bluntly, asymmetric games are just more hype in competitive play. The different characters in Street Fighter, the races in StarCraft, and the decks in Magic: the Gathering have all created tons of hype and excitement that wouldn’t have been possible with a single character, single race, and single deck that everyone plays.

Getting to the meat of the game quickly

This may not sound like an important property, but it really is in competitive play. The game needs to be as efficient as possible because if you have an event where you’re trying to get through many matches with many players (in swiss, or double elimination for example) then you need those matches to be as short as possible or else the tournament becomes too long to comfortably run. Every turn in the game should pull its weight. Even if you never play in a tournament, you should appreciate this anyway. Removing filler turns gets you to the fun that much faster.

Some deckbuilding games start you with what are basically blank cards in your deck, usually victory point cards that get added up at the end of the game. Puzzle Strike replaces those blank cards with your character chips. So your most interesting actions are there from the start, and you can actually start doing stuff on turn 1 and 2.

Exciting Moments Built Into the System

Any game that can hold up to competitive play is probably capable of generating exciting moments. That said, we can certainly influence how often these moments happen by adjusting the game design. Puzzle Strike is specifically tuned to intentionally create exciting moments often.

A lot of this is from the crash gem system, as described above. Players are inherently more powerful as they are about to lose, so close games are frequent. Another thing that makes exciting moments even more frequent is the way the game checks the lose condition. If you end your turn with a pile height of 10 or more, you lose, but you CAN have more than that during your turn. An opponent might send a lot of gems to you and you might start your turn with a total of 15 or more. Dire straits! But over the course of your turn, you might be able to do a huge combo that digs yourself down to 9 or fewer gems. The height bonus lets you draw the maximum number of chips in this case, so you’re actually more likely to pull off a spectacular turn that barely saves you.

Solid rules

This could be a whole article in itself, but basically game rules need to be very solid to allow experts to play as hard as they can. You can’t have rules that involve judgment calls of some third party. You can’t have rules that say you can’t make a certain kind of move “too much.” You can't require shuffling of cards that have different card backs. You can’t have rules about communication with other players that say “you can talk, but you can’t share certain types of information.” You can't have legal moves that make the game degenerate to play and then say it's "not in the spirit in of the game" to use those moves. There’s a whole lot of sloppy things you can’t do. Puzzle Strike is designed with serious play in mind, and has rules suitable for players who are trying their hardest to win.

Casual Play

For a game to have casual appeal, it actually needs some of the same things we just mentioned. Most importantly, it still needs interesting dynamics, it’s just that those must be apparent right away, even if you’re bad at the game. All the things that make Puzzle Strike interesting to experts still count here because even beginners can see how the crash gem system works.

Another element of casual play is being able to involve more players. Puzzle Strike has a 2v2 mode and a 3p and 4p free-for-all mode. The free-for-all mode is very interesting and I’d go so far as to say that it’s my contribution to the field of how to make free-for-all modes.

Free-for-All

A common problem with free-for-all modes is that they are too dominated by pre-game alliances. That means if you and a friend play with two other strangers, your ability to team up (even if it’s kind of unconsciously) with your friend can be too overwhelming. If a game is decided before you even start just because you have a friend in it, that’s poor design even for casual play.

Another common problem with free-for-all modes is that doing nothing is the best strategy. Let other players fight each other and weaken themselves, while you grow stronger. That’s really boring, yet it’s almost the default way that most free-for-all games work.

Finally, kingmaker and lame duck are common (and bad) qualities in free-for-all games. Kingmaker is when a player who can’t possibly win gets to decide who does win. Lame duck is when a player who can’t possibly win is technically still playing. This feels stupid and pointless to the lame duck player, and allowing this situation to happen at all greatly increases the chance of kingmaker situations.

Puzzle Strike’s free-for-all mode avoids and minimizes ALL of those problems. It works in a fairly unusual way. You are able to crash gems at any opponent you want, but you can’t actually gang up to eliminate someone that way. That’s because there’s no player elimination; instead, the game ends the moment that anyone ends their turn with a full gem pile. The player with the least gems in their gem pile wins.

Whenever someone is about to lose in this free-for-all mode, someone else is about to win. And anyone else playing has incentive to help the would-be loser to prevent the game from suddenly ending. They can do that by counter-crashing for that victim to help them out. To put it another way, whenever you’re about to lose, you always have at least one friend in the game whose incentive it is to help you. Who that friend is depends on the pile heights and what’s happening in the game, not on who you’re real life friends with outside of the game.

Furthermore, there isn’t really lame duck. If you’re still playing, you can still win. And the lack of lame duck means that kingmaker is minimized. There’s even a special rule to minimize it more: if you have a ton of gems in your gem pile and you’ll surely lose, you can’t just crash some in such a way as to decide the winner. Your crashed gems remain “floating” until you prove that you can dig yourself out below 10.

Components

I talked a lot about game dynamics that are fun in a casual setting, but there’s also a tactile and visual element to it all that’s really important.

Boards

The boards in Puzzle Strike help you organize your gem pile and other zones, and have some helpful reminder text. They also look like a video game (like Puzzle Fighter sort of) and that gets you in the spirit of things.

Screens

The screens (or “shields”) let you hide your chips from other players if you’re having trouble holding them in your hand. They’re pastel colored and they each depict a different game rule in Puzzle Strike in a fun way using 8-bit versions of the characters.

Chips

Most deckbuilding games are playing with cards. These types of games require a lot of shuffling though, and the form factor of chips allows you to draw them from a bag without having to worry so much about frequently shuffling cards. Players who are bad at shuffling, and even players who are good at shuffling have often said the unusual form factor is kind of charming.

The Box

It’s kind of bold to have a pink box! The cute characters and distinctive pink box have gotten a lot of people to try the game who would have been intimidated by a more serious looking box. Silly as that sounds, the packaging matters!

Conclusion

The crash gem system that’s the core of Puzzle Strike captures some of the best qualities of the Puzzle Fighter. It’s strategically interesting to experts, yet still accessible to beginners. Puzzle Strike is designed to be a solid tournament game, yet didn’t really have to sacrifice much of anything to have plenty of casual appeal too.

You can get the tabletop version here or play it online here.