In some ways, trolling may be the most effective communication of all.

A troll is a person who posts or chats on the internet with the intent of stirring up trouble and getting emotional responses. A troll is not concerned with speaking the truth, nor with speaking lies. The truth value of statements isn’t important at all to a troll, only the amount of trouble their statements can cause.

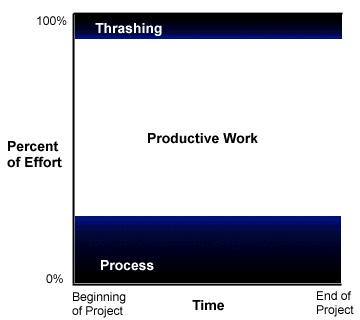

Another aspect of trolling is efficiency. Ideally, the troll gives very little input to the system, but creates a large stir from it. Think of it like giving your opponent a bag of nonsense, but the opponent can’t simply open the bag and say “oh, that’s nonsense.” Instead, the nonsense is wrapped up in an intricate puzzle that takes pages of text to unravel and defend against.

James Cameron is a man clearly dedicated to his craft, but then again so was Jim Jones. But Cameron had much better results. Eleven fewer people died from cyanide poisoning.

—Mr. Plinkett

Is Trolling Bad?

I know a grandmaster troll. His name is garcia1000. He says that trolling is like sex: if you force it on someone, that’s bad, but if it’s consensual, then both parties enjoy the activity. Over the years, we’ve developed many “chat techs” that are handy language tricks for trolling. Playing with intentionally deceptive language is really fun, and I think there’s some value in it too. When someone tries to use this stuff on you, you’re ten steps ahead of them if you’re well aware of all these tricks. You can also incorporate these rhetoric tricks into your writing as jokes, or for real if you’re a news journalist.

Try consensually trolling your friends and develop your skills together.

Chat Techs

Implying a Connection When There Isn’t One

One of the easiest ways to troll is to imply a connection to something bad when there is actually no connection at all. The victim will have to go through all sorts of trouble to explain why there is no real connection.

He eats pizza without a knife and fork, like an animal in a zoo would.

Wilt Chamberlain had over 20,000 career rebounds. Meanwhile Governor Schwarzenegger had 0, the same number as Hitler.

DOTA has a song about it. So does killing cops.

Ian isn’t a pedophile, at least that’s the story so far.

Blake says he’s not racist, but Don Imus said that also.

By moving out of our cramped apartment into the larger one, we’ll finally have more breathing room, or “lebensraum” as the The Nazis called it.

Connection to Stock Price

Amazon.com Inc. [AMZN -1.89%] is staying the course with a new line of Kindle Fire tablet computers that undercuts competitors like Apple Inc.’s [AAPL +0.55%] iPad on price. (source)

It sounds like the stock prices demonstrate that Amazon are idiots for undercutting Apple’s price, but the stock price changes are not because of this specific move. If Jeff Bezos cured cancer tomorrow, the Wall Street Journal article would read:

Jeff Bezos Cures Cancer [AMZN -1.89%]

Mr. Bundesen says he chauffeured Grumpy Cat around Austin in a black BMW [BMW.XE +2.91%] X5, with tinted windows. (source)

Did Grumpy Cat directly affect BMW’s stock price? Let’s go with yes.

Grumpy Cat

True Goodness

Mother Teresa has performed many good deeds, but how many of them were truly good?

Aphotix has made many useful contributions to balancing the Yomi card game, but how many of them were actually useful?

Lack of Perfection = Badness

garcia1000, creator of numerous troll techs, has never created a single perfect troll.

Lady Gaga has written, directed, and sung many hit songs but she has yet to create any song without flaws.

The Absence of Something

The President will be holding a dinner at the white house next week. The best chefs in France will not be attending.

The ACLU will not be attending.

The League of Women Voters will not be attending.

EA held their company picnic last Friday. The IGDA, an organization that fights for quality of life issues on behalf of game industry employees, did not attend.

The downtown clinic opened its doors to all who needed medical attention, regardless of their age, class, or race. The clinic helped no black people yesterday.

In each case, it sounds like the lack of these people attending implies their disapproval. Actually it implies nothing and there’s no reason to expect them to have attended.

Not Immediately Available

Pop star Justin Beiber visited the Anne Frank museum and said “Hopefully she would have been a Belieber.” It’s possible this line made sense in the context in which it was said, but a news story can make it (or anything else) automatically look bad with this line:

Bieber's representatives did not immediately respond to CNN's request for comment Sunday, but visitors to the Anne Frank Facebook page had plenty to say.

Justin Beiber

“Not immediately responding” sounds like some sort of admission of guilt, when it actually means nothing at all. Beiber is guilty of not immediately responding many times though:

- About his retirement

- About being punched by Orlando Bloom

- About breaking up with Selena Gomez

- About an attempted robbery

- About walking unsteadily during a sobriety test

- About police raiding his home for drugs

- About reckless driving

I don’t know what Justin Beiber did or didn’t do, but the “didn’t immediately respond” tech is great to combo with a false accusation.

Not the First Time

Sony's PlayStation Network servers crashed today. This isn't the first time that’s happened.

Even if it only happened once before, the statement implies it’s been multiple. Also, “it’s not the first time” can put the phrase "and it won't be the last" into reader's mind. The statement is factually correct though, even if it happened only one time before, so it can't be challenged.

Not the Last Time

Marissa Meyer

Yahoo’s CEO Marissa Meyer banned employees from working from home, which was controversial. A “news” article ended the story with the sentence:

Her remote working ban may not be the last controversy of her rule. (source)

So now she’s held responsible for future, unspecified controversies! Also, it’s a nice touch to call her tenure as a CEO “her rule.” This implies it’s some dictatorial horror, when it’s actually the job of a CEO to “rule.”

This tech also combos well with accusations. Being accused of something doesn’t mean you did it, especially if the accusation is totally fabricated or ludicrous. But if we add that it “may not be the last time,” then it sounds more damning.

McDonald’s was accused of using rat meat for 20% of its burgers, and this may not be the last we hear of it.

Some people say Google is guilty of tax fraud, while others say this may not be the last time we hear this accusation.

That's also an example of “weasel words.”

Weasel Words

Weasel words are a way of using vague language and anonymous authority to assert something that’s impossible defend against because it’s too vague to even know what it means.

Some people / experts / many say that The Hobbit is the worst movie of modern times.

Which people? How do they know? What standard was used?

It is said that the this article is the definitive one on fun trolling language, though there are some who claim otherwise.

Who said that? They said it as fact? Also those who say otherwise only “claimed” it, so their viewpoint is diminished.

Examples

"A growing body of evidence..." (Where is the raw data for your review?)

"People say..." (Which people? How do they know?)

"It has been claimed that..." (By whom, where, when?)

"Critics claim..." (Which critics?)

"Clearly..." (As if the premise is undeniably true)

"It stands to reason that..." (Again, as if the premise is undeniably true—see "Clearly" above)

"Questions have been raised..." (Implies a fatal flaw has been discovered)

"I heard that..." (Who told you? Is the source reliable?)

"There is evidence that..." (What evidence? Is the source reliable?)

"Experience shows that..." (Whose experience? What was the experience? How does it demonstrate this?)

"It has been mentioned that..." (Who are these mentioners? Can they be trusted?)

"Popular wisdom has it that..." (Is popular wisdom a test of truth?)

"Commonsense has it/insists that..." (The common sense of whom? Who says so? See "Popular wisdom" above, and "It is known that" below)

"It is known that..." (By whom and by what method is it known?)

"Officially known as..." (By whom, where, when—who says so?)

"It turns out that..." (How does it turn out?¹)

"It was noted that..." (By whom, why, when?)

"Nobody else's product is better than ours." (What is the evidence of this?)

"Studies show..." (what studies?)

"A recent study at a leading university..." (How recent is your study? At what university?)

"(The phenomenon) came to be seen as..." (by whom?)

"Some argue..." (who?)

"Up to sixty percent..." (so, 59%? 50%? 10%?)

"More than seventy percent..." (How many more? 70.01%? 80%? 90%?)

"The vast majority..." (All, more than half—how many?)

Dog Wouldn’t Understand

If you explained global warming to a dog, the dog wouldn’t understand.

While James claims he's not racist, even his dog Woofy can't be sure of that.

Playing with the Likelihood of Things

It's possible Jeremy is sane like a normal person. We can't dismiss that possibility out of hand.

You can use the teapot fallacy to make anything, no matter how astronomically unlikely, have a 50% chance of being true:

There either is or isn’t a teapot orbiting Jupiter. 50/50 that it’s true.

There either is or isn’t a supernatural being who takes interest in my personal fortunes. Again, 50/50.

Saying Things Are Similar When They Aren’t

I think insisting on high quality games is similar to insisting on serving white people only. In both cases, you're insisting on something.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was in charge of people, much like how Stalin was in charge of his.

Jill took several books from the library without paying. Robbers would have done the same thing.

John was good with building things with his hands, much like the Unabomber.

Admitted

Use “admitted” to make anything sound bad:

Bob admitted he bought the cheaper fabric softener.

Jane admitted she had pizza for lunch.

Andrea admitted she was intimately familiar with how to spell “pedophilia.”

We asked Greg if he committed the robbery, but he admitted nothing. (Also, he did not immediately respond.)

Combine this with the “absence of something” tech for even greater effect:

Charlie admitted his iPad didn’t contain any e-books against racism. Charlie also admitted he did not attend the recent ACLU rally about civil rights.

Comparing Numbers and Degrees

When you say how good or how big or how numerous something is, say it’s more than an absurdly low value. This makes it sound like it probably is that low value.

The French Army had at least 3 soldiers.

Game of Thrones wasn’t the worst of HBO’s tv series, I’ll give them that.

When compared with the most vile and debauched scoundrels, President Obama is a lightweight. He did keep Guantanamo Bay open though.

The makers of the game BlazBlue were passionate about their craft, but then again so were Texas Governors. BlazBlue, a game with more than 6 fans, caused 137 fewer deaths by lethal injection.

Gordon Ramsay cares a lot about his craft, but then again so does Godzilla. Ramsay, who has 13 restaurants rated at least one star, had much better results. He leveled Tokyo 9 fewer times.

Being Paid For Things

The policeman, who is paid $52,000 per year, did not respond to the 911 call in time.

Throwing in salary numbers irrelevant to the situation makes it sound even worse. Being paid is bad.

The heart surgeon said the surgery was necessary to save Mr. Martinez’s life (he was paid to do the surgery).

You were paid to do something, implying that you're only doing it for the money like a hired shill. Being paid is bad.

Wolfgang Puck's signature herb-roasted chicken tastes like charred cardboard, and I could do a better job blindfolded,” said Ellen Kubolski, who has never been paid to cook anything in her entire life.

You haven't even been paid to do something, so your skills are very bad. Not being paid is bad.

Why Not Just?

Why not just implement a new feature in the game?

Why not just redo all the art in the game?

Why not just let prisoners come and go on the honor system?

Why not just have the CFO guess what the taxable revenue is this year?

“Why not just” is a powerful combo of two separate fallacies. First, “why not” implies that any insane idea should be the default. Why isn’t it ALREADY this way? Second, “just” is a red flag word for anyone who does any kind of work. “Just” implies that a task is a small amount of work no matter how much work it actually is. Finally, the “just” hides any and all negative fallout from the ripple effects of the proposed change. For example, if the CFO “just” guesses about the taxable revenue, she might end up in jail.

In Some Ways

Put “in some ways” before a statement to make it true no matter what. Even if it’s apparently false, the burden is now on the reader to construct some elaborate case where it could be true. If they can’t, it’s their fault for lacking imagination.

In some ways, having one of the worst health care systems in the world is a great boon to the United States.

In some ways, lack of exercise makes Jim even stronger.

In some ways, knowing more about a subject means you know even less about it.

In some ways, this article makes you a better writer.

Advanced Combos

The game Skullgirls sold fewer copies than the number of people in prison in the USA, a figure which speaks for itself.

Skullgirls could have given a copy to every one of those prisoners, but designer MikeZ admitted that he chose not to, which just continues the tragic trend.

We can't say if MikeZ is ultimately responsible for the prison riots, but we can say his decision to exclude prisoners from getting free copies of Skullgirls has been a long tradition of his.

Graham lacks the ability to sculpt believable statues from a single slab of marble, much the same way that animals in a zoo can't. This may not be the last time Graham is mentioned in connection with animals of subhuman intelligence.

This one is especially good because it manufactures an insane connection, then says it may not be the last time we hear it, citing itself as the reference.

I approve of this new tech, like Einstein who approved many new breakthroughs.

—garcia1000

You can think of these troll techs as a kind of vaccination. By injecting them into your bloodstream, you become more immune to them being used on you. Try injecting them into your writing, twitter, and friends. Enjoy!