When writers are asked how to write well, they often reflexively talk about their childhood and how they became writers. James Joyce did it, George Orwell did it, and Steven King did it. I thought this was a strange pattern at first, but now I understand it. Writing well is not just about clarity and omitting needless words—it goes all the way down to the core of a person, and so writers tend to tell you about who they are to explain how or why they write as they do.

Joyce, Orwell, King

Growing Up

Many of us had that one teacher. That one horrible teacher who either hated you, or you hated, or both. For me, that teacher was Professor Cooney of the MIT writing department. In my entire academic career, she stood out as the most infuriating.

Before we get to her, I’ll tell you about what happened eight years earlier, in 7th grade. I was in Algebra I, an advanced math class for a 7th grader, because my 6th grade teacher said I was good at math. I had no idea I was good at math before that as I wasn’t particularly good at arithmetic. (Just as writing isn’t spelling—math isn’t arithmetic, so I’d be ok in that math class.) After the first test in that class, my friend got a perfect score and I didn’t do very well. I thought back to all the episodes of Star Trek I watched every weeknight at midnight during the summer, and about how Mr. Spock would have gotten a perfect score, too. And how could anyone not get a perfect score? You just follow things through to their logical conclusion and you get the right answer. From that day on, I was good at math and I liked it (and science, too). That’s where my head was.

Except for a girl, that is. Her name was Jenny. Jenny and I loved ironic double meanings. I talked to her on the phone often, for hours. She was there when the wet cement of my personality was hardening. We each delighted in the use of language, always saying things without saying them. I learned to choose my words carefully with Jenny, and to give them just the right shade of meaning. She gave me plenty of practice, too, and I've had a careful eye (and ear) for language ever since.

I got an A on every essay in every English class all four years of high school. I was not part of the literature kids' tribe though. I wasn’t into poetry or literature or reading any of that squishy stuff. I was the math and science kid who stopped by English class to get his A, usually causing a lot of trouble and debate. English teachers and I never had much regard for each other, and I knew some of them absolutely cringed at giving me those A’s, but what else could they do? I remember thinking at one point in high school that it would be an ultimate joke of the universe after all my hating of English classes if I would somehow end up a writer instead of a mathematician or physicist. (Note to the universe: nice one.)

By the time I encountered Mrs. Cooney, I knew how to write and I knew how to get an A on a writing assignment. I started her class by writing a short story in the style of Jack London (my choice) about a man and his dog. I thought it was pretty good. She hated it. The narrator actively judged the man in the first and last sentence of the story, on purpose. She hated that even more.

I didn’t know exactly why she hated it, and I wasn’t used to that kind of reaction. She kept saying, “It’s not literature! We write literature here.” It took me the whole semester to even get an inkling of what literature meant to her. It seemed mostly to mean, “boring stuff written by the students who Professor Cooney personally likes talking to in class.” She said my story was too fake and she wouldn’t even accept it, much less grade it. She said I had to write another story instead.

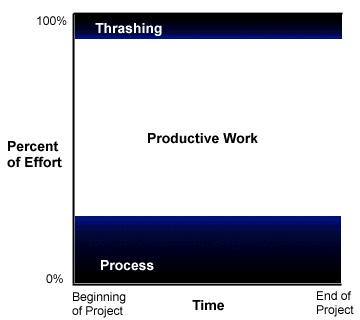

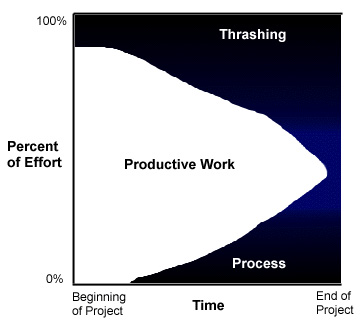

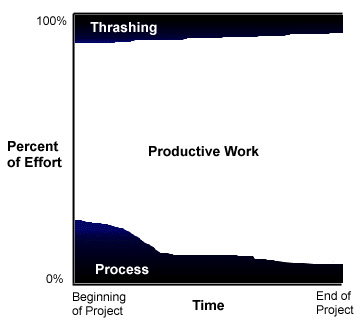

I may have some ability at writing, but writing takes me a very long time. What’s worse is that I can’t compartmentalize it from the rest of my life. When I write something, the actual time I spend typing is between 1% and 5% of the total time investment. The rest is spent day dreaming about it, thinking of how the ideas will go together, about this sentence that should appear halfway through, about things I might need to research first, and so on. And when all that’s sorted out, I still have to wait around for the moment when I’m not tired, hungry, or distracted. Then I have to keep waiting even more until I’m also inspired. I believe at least three of the planets must be aligned, too, or two plus a moon at the least. The point is, writing another story was a major time investment.

I don’t remember what happened with that second story, but I bet she hated it too. On the assignment after that, I wrote a story about a man who took a long journey to find a magic coin, but there was some kind of trick about how the guy who told him about the coin was not who he seemed. Yeah, she hated that one even more. I spent a very time long on that one making sure it was well-written. She said it was “genre writing,” not literature, and that it could appear alongside any other fantasy writing on a store shelf and blend right in. (Is that an insult or a compliment?) Apparently literature couldn’t contain magic. It also couldn’t be a mystery, couldn't have too much action, and could hardly have any violence, I would later learn. Meanwhile, we read a story about two girls who lived in an isolated countryside and used to play together as children, then they tried to keep in touch as adults but their lives had diverged too much to make the same kind of connection. Now that was literature, she said. I have to admit, even though it had no apparent point, it did feel real when I read it.

She made me write two stories for every one that anyone else wrote in that class. It was an incredible amount of time and work and she hated all of it. I wondered why she made me do all that if I was so terrible, yet none of the other students had to.

For my final assignment in that class, I decided to write something I knew enough about to bring to life. I wrote about a young man who was entering his first Chess tournament and the various personalities he encountered at the event. The antagonist was a tricky jerk who had enough experience with how the events were run to mess with the main character’s mind. They would face each other in the tournament, and I even went through the trouble of coming up with a real Chess situation that was interesting in itself, and that illustrated the mental sparring between the characters. And I took great care describing this so it wouldn’t be boring or overly technical for non-Chess players.

Guess what, she hated it. She said I was a failure as a writer and I’m guessing she added that I’d never amount to anything, for cliché’s sake. She said, and I quote, “You are a master of linguistic flourishes, but you ultimately have nothing to say.” Wow! Yes, she really said it, exactly like that. A master of linguistic flourishes…but ultimately with nothing to say. That was a lot of years ago, but I remember it exactly.

I began to wonder if she was right. She was a close-minded jerk to me, sure, but what was I trying to say with that story about the guy and his dog or about the magic coin? Maybe nothing. At least the Chess story had some point. The year after that in another writing class, I decided to write a comedy about depression (challenging!) and another story about someone who is trapped in his own superstitions, but ultimately realizes that he controls his own destiny in life. I was at least trying to really say something.

Having Something to Say

A few years later, I had a lot to say. I had competed in and organized numerous video game tournaments, and I kept seeing the same annoying losing attitudes. The players I hung out with didn’t have these hangups, but the ones on the periphery often had the whole concept of competition wrong. So I wrote Playing to Win. I finally had something to say, and I never got so much attention for writing anything until then.

William Strunk, Jr. famously said to omit needless words. I’ve come to look at this in a new light, and when I see writing that doesn’t really say anything, I wish all the words were omitted. There are a lot of mechanics involved with writing well, but it doesn’t amount to much unless you have something to say. Having something to say often goes along with taking a stand on something. Research what you’re interested in, live life and accumulate experiences, stand up for what you think is right and fight against what you think is wrong. It takes a certain kind of person to do that. Writing is often about revealing a truth or exposing a lie, so it’s no wonder that so many writers are the kind of people who don’t care what people think of them—they care about the truth and saying what they have to say. I don’t mean pop novelists either, I mean Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell. Even Richard Feynman was a great writer in this regard when he wasn’t busy being one of the world’s leading physicists. He even wrote a book called What Do You Care What Other People Think?

Learning the Craft

I worked with an amazing graphic designer for a while until he quit and went to another company. In our last conversation, the day before he left, I asked him how he became so good. How is it that he’s so much better at what he does than most others who try to do it? He said in art school, there was one Korean guy in his class who really shouldn’t have been in there. The Korean guy already took these classes in his own country, but his credits didn’t transfer over for some reason. My friend said he always studied the Korean guy, how he made this line, how he made that shadow, whether he added decoration here or not, and so on. He told me that when some students presented their projects, they had some big artistic vision they were trying to communicate, but they always fell so far short. My friend never focused on that—he focused on execution instead. His reasoning was that once he had mastered the mechanics of graphic design, he would then be able to think about what artistic statements he wanted to make. I did not take such a conscious journey as my graphic designer friend, but perhaps the result is the same: first, how to put sentences together properly, then having things to say.

Putting It All Together

There have been years where I had a lot to say, where I wrote many articles about game design. There have been other years where I was too consumed with working to say much of anything. Now and then, I feel the need to share some ideas, but I don't do it unless I really have something to say.

When I sit down to write, I don’t think about Jenny and the nuances of language I practiced with her all those years ago. Caring about exact shades of meaning is second nature now. And I don't think about Professor Cooney anymore either, but for a while I did. “A master of linguistic flourishes but ultimately with nothing to say? I’ll show her," I'd sometimes think. I’ll prove to her that I do have something to say, and that I’ll say it no matter what the consequences or what anyone thinks.

Maybe being fueled by such a negative fire was a bad thing, but being fueled by no fire is far worse. It's hard to work to have clear thoughts and to express them clearly, so some passion to get you through it—no matter what the source of that passion is—helps greatly. I’ll leave you with this quote from a writer who has sold over 350 million books:

You can approach the act of writing with nervousness, excitement, hopefulness, or even despair—the sense that you can never completely put on the page what’s in your mind and heart. You can come to the act with your fists clenched and your eyes narrowed, ready to kick ass and take down names. You can come to it because you want a girl to marry you or you want to change the world. Come to it any way but lightly. Let me say it again: you must not come lightly to the blank page.

—Stephen King