I've only said "Wow!" a few times in the last couple decades of playing games. One of those times was for the breakthrough Super Mario 64, a game that took action/platforming into a 3D world and made it work. It's fitting that I said it again over its (true) sequel, Super Mario Galaxy, a game that took action/platforming even more into 3D and made that work, too.

Why is Mario Galaxy so good and what can we learn from it? To borrow some terms from Nicole Lazzaro's four kinds of fun, Mario Galaxy has hard fun, easy fun, and social fun as well as the ability to evoke the emotions of surprise and wonder.

Hard Fun

Gamers know this kind of fun all too well. This is the fun of overcoming obstacles and attaining goals. When you succeed at an especially difficult challenge, the Italian word fiero describes the emotion you feel as you raise your fist into the air triumphantly. Mario Galaxy has 120 stars to collect, offering plenty of this type of fun.

Hard fun is so common in games that the only thing worth noting here is how well Mario Galaxy informs the player about exactly which goal he's going for, which goals are completed, and how many goals are left. I think this clarity magnifies the fiero aspect of the game. Putting the tally of hard fun at center stage (the number of Mario Stars, out of 120, you've collected) makes it all the more satisfying to achieve the goals.

Easy Fun

Ironically, this fun is much more rare in games. This is fun that's not bound up with winning or goals. The entire Nintendo Wii system has an advantage here because the motion-sensing Wiimote lends itself to easy fun.

Collecting the star bits (the colorful, glowing ammunition that bounces around everywhere) with the Wiimote's pointer is easy fun. Shooting the star bits at enemies is easy fun, though hardly ever required to achieve goals. Using the left-right-left-right gesture to do the spin attack is easy fun.

Another part of easy fun is exploration and variety. Some of the gameplay variety in Mario Galaxy includes:

- Flying with the bee suit

- Shooting fireballs with the fire suit

- Creating frozen platforms and ice skating with the ice suit

- Becoming a ghost who can turn invisible and float with the ghost suit

- Jumping very high with the spring suit

- Riding a manta ray on the water in a race

- Riding a turtle shell underwater in many situations, including races

- Balancing on a ball as you navigate through a level

- Flying with the red star suit

- Numerous tricks of gravity that vary across several levels

Just the moment-to-moment interactions involved with these things are fun, without even considering how they are used in the context of hard-fun-goals.

Social Fun

Mario Galaxy is primary a one-player gamer's game (lots of hard fun), but it includes a brilliant two-player feature that will surely become a standard. Some dismiss this feature as "tacked on," but something that strikes such an exactly correct note was surely a carefully considered feature. The two-player co-pilot feature is intended for a non-gamer to enjoy the game alongside a gamer. It adds a lot of social fun to a game that would otherwise have nearly none of that kind of fun.

The second player uses their own Wiimote, but does not use the nunchuck add-on (what non-gamer would want to anyway?) The second player gets their own cursor on-screen that can collect the many star bits littered throughout most levels. The second player (as well as the main player) can shoot these star bits at enemies. The star bits are basically like a shared pool of ammunition, and the second player can add to that pool and deplete it by shooting.

The greatness of this feature is in the details. First, the main player never actually needs the help of a second player, so this isn't like forced grouping in an MMO. Also, the second player can enter and leave the game at any time without any annoyance or stop in the action. When the co-pilot is helping, they feel like they are contributing because collecting star bits and shooting enemies is at least somewhat helpful.

Also, there are several times in the game where a special NPC appears who asks you to contribute a bunch of star bits in order to unlock a new level. This means you can't completely ignore collecting star bits, and again, the co-pilot is contributing by collecting them. There are certain times when the main player is too engaged in hard fun platforming to be able to collect star bits at the same time, and this is yet another situation where the co-pilot can contribute.

The role of the co-pilot is kept from having too much impact because shooting enemies does not actually kill them (it momentarily stuns them). Also, even without a co-pilot, any hardcore gamer worth his salt would be able to get enough star bits that no co-pilot is needed. But the non-gamer co-pilot doesn't know that!

Finally, the co-pilot's role consists entirely of easy fun. There is no way to actually fail at anything as a co-pilot. You just collect star bits whenever you feel like it, and shoot enemies if it seems like it would help.

If at any point your co-pilot would prefer to sit there and do nothing or put down the controller and check on the stove, that doesn't cause any problems. Because the co-pilot has no pressure, it's easy to suck in a non-gamer. You get their in-game help, you get their observations about where a secret might be hidden, and most importantly, you'll actually communicate back and forth about things (aka social fun).

Surprise and Wonder

In addition to these types of fun, Nicole Lazzaro also mentions several types of emotions that come up in games. I already mentioned fiero, the emotion you feel when you achieve something difficult. Mario Galaxy also creates the very rare game-emotions of surprise and wonder. That's quite an accomplishment considering the game's genre is well-worn territory, but the twists on gravity are interesting enough that sometimes you just sit back and say "wow, that's cool!"

The surprise part is that you feel the wonder part several different times as the gravity tricks change. Just when you thought it was cool to run around the surface of spherical planets, you get to a room where "down" can potentially be any surface.

Then a level where you can flip switches to change the direction of gravity. Then a level where moving spotlights determine exactly where a different direction of gravity is "shining" on an otherwise normal level. There are enough surprises to go around, and I've already ruined most of them for you.

Craftmanship

There's a few pet issues I'd like to point out that Mario Galaxy does right.

Opening Sequence

The opening sequence is only a few seconds long, before you get to actually move around. Compare this to over 15 minutes in the excruciating opening of Paper Mario. The original God of War has an opening sequence of less than 60 seconds, showing that there are better ways of conveying story than forcing the player to watch a long cut-scene before a game starts.

Mario Galaxy conveys some of its story simply by showing speech bubbles over NPCs as you run by. You also unlock chapters of an in-game storybook as you progress through the game and you can read them whenever you want or not at all.

Inertial Frames

When you jump straight up while riding a train in real life, you do not slam into the back of the train; you land on the same spot as you jumped from. Physicists say that you are in the same inertial frame as the train, meaning that you're moving with it and your walking or jumping is relative to it.

You all know this instinctively and yet almost no platform games know this. I remember actually being shocked in the game Spider-Man 2 when my Spider-Man was on top of a car and I jumped straight up and landed on the car. "Wow, they know about inertial frames!" I said. At long last, Mario Galaxy knows about them too. You can finally jump straight up while riding a moving platform and land on the platform without worrying about it moving out from under your feet.

Wall Jumping

This is a small thing, but points to an important idea. In Mario 64, the wall jump move required good timing. You had to press jump just as Mario touched the wall, no sooner and no later. In Mario Sunshine, The New Super Mario Brothers, and Mario Galaxy, it no longer requires timing. When Mario touches the wall, he starts to slide down and you can press jump at any point during the slide to activate a wall jump.

Someone might say that the original harder wall jump was better because it "required skill." No one actually says that, though. Being able to do your moves is fun, and Nintendo realizes that making a move hard to do is a bad way to add challenge. Even when it's easy to execute a wall jump, there can be plenty of difficulty coming from the level or the situation you're in.

Maybe you have a time limit, or maybe there are some flame jets you have to wall jump past, or a hundred other things. Incidentally, this is the same logic I'm using in making the moves easier to perform in Super Street Fighter II: HD Remix. The moves themselves aren't meant to be the source of challenge, it's how and when you use those moves in the context of the game that's challenging.

Camera

I used to think that moving the camera around while you are in the middle of platforming was part of the game in Mario 64. I was good at this, and I considered it one of the skills the game was all about. Mario Galaxy removes this "skill" almost entirely because it has an amazingly good camera system. Almost all the time, the camera is pretty much where you want it to be. This is a similar concept to the wall jump mentioned above, in that the game is much better off creating difficulty in other places than wall jump execution or camera fiddling.

Mario Galaxy's camera is actually an amazing accomplishment. I saw a GDC lecture one year about camera systems in games from the guy who did the camera for Metroid Prime. That game also has excellent camera handling (and the best mini-map ever). You might say, "But it's a first-person shooter! There is nothing to the camera."

What you don't realize is that Metroid Prime has over 20 camera modes. When you're in an open area, it's a regular first-person camera. When Samus rolls into a ball, it's third person. Some ball-rolling areas have a side-view camera and basically turn the game into 2D gameplay. Going through a tunnel has a special camera, and some boss fights have another camera.

A Mario-style third person platform game has even more demanding camera needs than Metroid Prime. In 1996, I would have not even been able to imagine a camera for a 3D Mario game that was basically in the right place almost all the time.

When you consider that Mario Galaxy presents far more challenges to camera design than any other 3D platform game ever, it's that much more impressive that it succeeds. No matter which way gravity is going or which kind of crazy thing you're jumping around on, the camera seems to know where it should be. This is undoubtedly the result of endless hours of hand-tweaking of camera paths and some very smart logic to boot.

Even More Excellent?

It's a real jerky thing to take an excellent game and say, "I'm knocking it because it wasn't excellent in some other area that it didn't even attempt." I already cringe at that being done to me someday, so I apologize in advance for this, but I do wish Mario Galaxy were even more excellent.

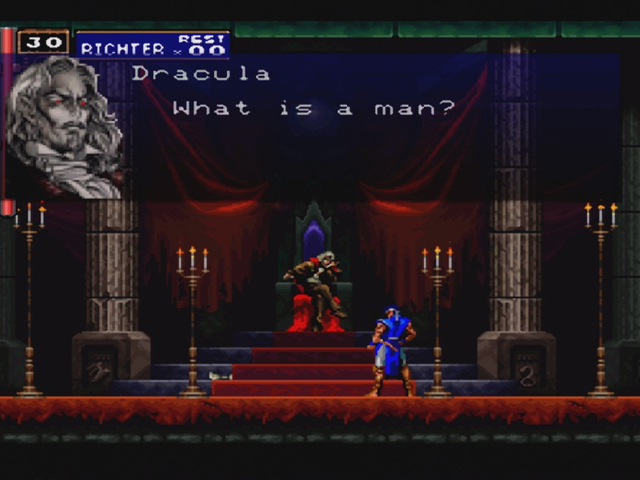

Before I say what that is, I'll tell you what I think is one of the best surprises in a video game. I mentioned this in my Pacing for Impact article, and I'm about to say the same spoiler now, for Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

When you beat that game (which only takes about 10 hours), you are lead to believe that you really reached the end. The game has been showing you what percentage of the map you've uncovered and it gets closer and closer to 100% as you work your way toward the final boss.

After you defeat him, the big reveal is that the entire castle where the game takes place turns upside down, and you have as much more gameplay ahead of you as lay behind. This isn't some cheapy "play the entire game again and get the pink weapon" trick like Ghosts 'n Goblins uses, though. All the stairs and chandeliers and everything else are now upside down, creating all-new puzzles even though the territory is familiar. The enemies are also all replaced by harder enemies. It's surprising and amazing that it works.

Back to Mario Galaxy. It has plenty of surprises of its own, but those take place within each of the many levels. If you take a zoomed out view of the game and just look at the structure of it, it's incredibly predictable. You very quickly realize that each world has 5 galaxies (levels). You realize how many worlds there are from the way the blank spots are arranged on the map.

Even though particular levels are surprising, the overall exercise on the most zoomed-out level becomes monotonous. I played probably the last third of the game on low volume while I watched reruns of Frasier and The Golden Girls on a second TV. (A less honest writer would not have admitted that!)

Mario Galaxy's purple coin missions were especially boring and tedious, even though some of them were very difficult. These missions have you return to familiar levels, but this time the levels have 100 purple coins in them that you must collect.

It's like a 10 cent version of the Castlevania's upside-down castle gold standard. I really wanted Mario Galaxy to break out of its own formula and surprise me on the macro level as much as it surprised me on the micro level. If a big, paradigm-shifting surprise belonged in any game, I think it's this one.

In some strange synchronicity, note that even this very article took a completely different direction than it started on. You expected it to be sheer glowing praise all the way through, then I started giving you may strange fantasies about what the game might have been. Nonetheless, as I mentioned earlier, Super Mario Galaxy iterates on its core mechanics in some of the most clever, polished, and beautiful ways possible.